What do Pulitzer Prints, a beached Venezuelan oil tanker,

a beached Venezuelan oil tanker, 8 American Steeplechase Champions,

8 American Steeplechase Champions, monkey testicle tissue,

monkey testicle tissue, Greta Garbo.

Greta Garbo. and Whale Cay

and Whale Cay have in common? All are connected in some way to female members of the Bostwick clan, a group of accomplished, interesting, and sometimes outrageous sisters, cousins, nieces and in-laws. These ladies owed their financial good fortune to family founder Jabez Bostwick, the first Secretary-Treasurer of the Standard Oil Trust (a company that spawned more than its fair share of heiresses). While also president of a railroad and member of several other corporate boards, Jabez gained a reputation as a modest man and devout Christian, dedicated to philanthropic pursuits amongst his robber baron peers. Given this was the Gilded Age however; he did build a grand Fifth Avenue mansion as well as Friedheim, a sprawling summer estate in Mamaroneck however. It was there he tragically died in August of 1892, along with two stable hands when run over by a coach they were attempting to push out of a burning carriage house during a freak stable fire. The large fortune he left behind provided comfortably for his grieving wife Helen (who inherited the bulk), two daughters, a son, and their future children.

have in common? All are connected in some way to female members of the Bostwick clan, a group of accomplished, interesting, and sometimes outrageous sisters, cousins, nieces and in-laws. These ladies owed their financial good fortune to family founder Jabez Bostwick, the first Secretary-Treasurer of the Standard Oil Trust (a company that spawned more than its fair share of heiresses). While also president of a railroad and member of several other corporate boards, Jabez gained a reputation as a modest man and devout Christian, dedicated to philanthropic pursuits amongst his robber baron peers. Given this was the Gilded Age however; he did build a grand Fifth Avenue mansion as well as Friedheim, a sprawling summer estate in Mamaroneck however. It was there he tragically died in August of 1892, along with two stable hands when run over by a coach they were attempting to push out of a burning carriage house during a freak stable fire. The large fortune he left behind provided comfortably for his grieving wife Helen (who inherited the bulk), two daughters, a son, and their future children.

The eldest was Dorothy Stokes Bostwick, born in 1899 to Albert C and Marie Stokes Bostwick. Growing up with four siblings at 801 Fifth Avenue in what was by then a small enclave of family mansions at 61st street,

her happy childhood was undoubtedly marred by the death of her father, who died young in 1911. This also meant that when Helen Bostwick died in 1920, her father’s share of her grandmothers $29,000,000 estate passed directly to Dorothy and her siblings, making her a very wealthy young woman. In 1922, papers announced the young heiress’s marriage to W.T. Sampson Smith (grandson of rear admiral William T Sampson) in Gilbertsville, NY, a town founded by her mother’s second husband’s family. The couple split their time between residences in Cooperstown New York, and Short Hills New Jersey, where Dorothy employed the all female firm of Wodell and Cottrell to design her gardens. A skilled yachtswoman, she was a good match for her husband, a builder of International Star Class racing yachts in the 1920s and 30s. The two were fixtures on the international powerboat racing circuit. She also became fascinated with the autogyro (a precursor to the modern helicopter)

her happy childhood was undoubtedly marred by the death of her father, who died young in 1911. This also meant that when Helen Bostwick died in 1920, her father’s share of her grandmothers $29,000,000 estate passed directly to Dorothy and her siblings, making her a very wealthy young woman. In 1922, papers announced the young heiress’s marriage to W.T. Sampson Smith (grandson of rear admiral William T Sampson) in Gilbertsville, NY, a town founded by her mother’s second husband’s family. The couple split their time between residences in Cooperstown New York, and Short Hills New Jersey, where Dorothy employed the all female firm of Wodell and Cottrell to design her gardens. A skilled yachtswoman, she was a good match for her husband, a builder of International Star Class racing yachts in the 1920s and 30s. The two were fixtures on the international powerboat racing circuit. She also became fascinated with the autogyro (a precursor to the modern helicopter) and in 1942 became the first woman in the United States to obtain a helicopter license. Dorothy’s interests weren’t limited solely to the sporting world either. A lifelong painter and sculptor, she went on to publish "Passing Thoughts," a collection of her poetry and drawings. Divorcing her first husband, Dorothy later married Joseph Campbell, vice president and treasurer of Columbia University, later Comptroller General of the United States. After an incredibly full life she passed away peacefully in 2001 at the age of 101. Despite all of her accomplishments, it is impossible to find images of her online, following the spirit of the old money adage that a lady’s name should appear in print three times, upon their birth, marriage, and death.

and in 1942 became the first woman in the United States to obtain a helicopter license. Dorothy’s interests weren’t limited solely to the sporting world either. A lifelong painter and sculptor, she went on to publish "Passing Thoughts," a collection of her poetry and drawings. Divorcing her first husband, Dorothy later married Joseph Campbell, vice president and treasurer of Columbia University, later Comptroller General of the United States. After an incredibly full life she passed away peacefully in 2001 at the age of 101. Despite all of her accomplishments, it is impossible to find images of her online, following the spirit of the old money adage that a lady’s name should appear in print three times, upon their birth, marriage, and death.

Dorothy’s younger sister Lillian lived a higher profile life, thanks in part to her second marriage. Her name first appeared in the papers in 1928 upon her engagement to Robert V. McKim of Aiken South Carolina. When they married later that year at Church of the Transfiguration the Times obliquely noting that it came as a surprise to many, the couple having broken off their engagement several months before. Nine years and three daughters later, Lillian made the papers again in 1937 with a Reno divorce from McKim followed by a quick wedding to court tennis champion and steel scion Ogden Phipps a few weeks afterward. This made Lillian, already wealthy, now a member of one of America’s richest families (it was rumored Ogden paid Robert a million dollars to divorce her). Along with brothers Pete and Dunbar, Lillian built and operated Bostwick Field in Old Westbury New York where they hosted international polo matches, to which the general public was invited free of charge, in an effort to democratize the sport, quite a novel concept to their peers!

Her name first appeared in the papers in 1928 upon her engagement to Robert V. McKim of Aiken South Carolina. When they married later that year at Church of the Transfiguration the Times obliquely noting that it came as a surprise to many, the couple having broken off their engagement several months before. Nine years and three daughters later, Lillian made the papers again in 1937 with a Reno divorce from McKim followed by a quick wedding to court tennis champion and steel scion Ogden Phipps a few weeks afterward. This made Lillian, already wealthy, now a member of one of America’s richest families (it was rumored Ogden paid Robert a million dollars to divorce her). Along with brothers Pete and Dunbar, Lillian built and operated Bostwick Field in Old Westbury New York where they hosted international polo matches, to which the general public was invited free of charge, in an effort to democratize the sport, quite a novel concept to their peers!

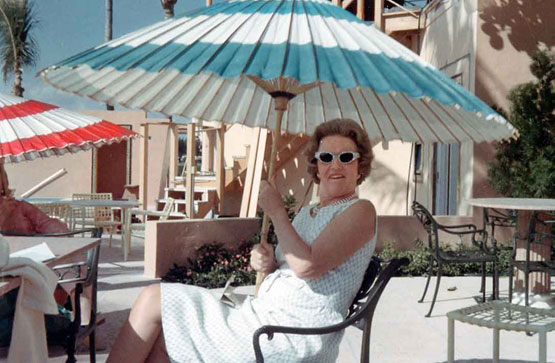

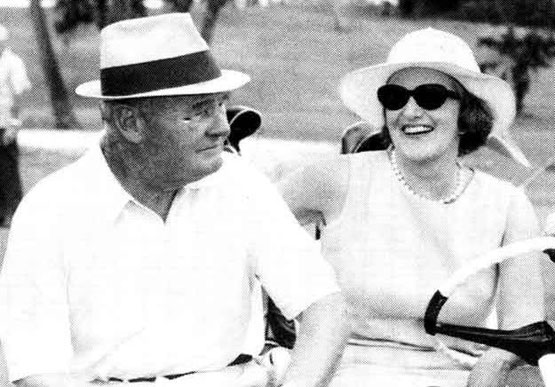

She found a kindred horsey spirit in her new husband. He focused on buying and racing flat track horses, whil eLillian purchased and raced steeplechase racers. Mrs. Phipps’s horses won the American Grand National eight times between 1951 and 1987, and owned two horses that were inducted into the U.S. Racing Hall of Fame. The couple was to be fun and gregarious,

and owned two horses that were inducted into the U.S. Racing Hall of Fame. The couple was to be fun and gregarious, entertaining grandly in their many residences they frequented, including New York City, Long Island,

entertaining grandly in their many residences they frequented, including New York City, Long Island, Saratoga Springs,

Saratoga Springs, Palm Beach

Palm Beach and Summerville, South Carolina.

and Summerville, South Carolina. She is credited with helping to launch the decorators Robert Denning & Vincent Fourcade, whom she used for all of her homes from they time they lanched their firm. While Lillian undoubtedly earned her spot in the Heiress Hall of Fame through her own merits before she passed away in 1987, her most enduring legacy was established indirectly, through one of her children. Her pretty middle dauguter married a man who owned several orange groves in Florida. Having an entrepreneurial spirit, she opened a juice stand in Palm Beach. Finding the whole business messy, she designed a sleeveless shift dress made in bright, colorful cotton prints to help hide the stains that came from squeezing oranges. Her customers loved her designs so much that she started selling them as well. She soon launched a fashion line under her married name, "Lilly Pulitzer", and the rest is of course, preppy fashion history.

She is credited with helping to launch the decorators Robert Denning & Vincent Fourcade, whom she used for all of her homes from they time they lanched their firm. While Lillian undoubtedly earned her spot in the Heiress Hall of Fame through her own merits before she passed away in 1987, her most enduring legacy was established indirectly, through one of her children. Her pretty middle dauguter married a man who owned several orange groves in Florida. Having an entrepreneurial spirit, she opened a juice stand in Palm Beach. Finding the whole business messy, she designed a sleeveless shift dress made in bright, colorful cotton prints to help hide the stains that came from squeezing oranges. Her customers loved her designs so much that she started selling them as well. She soon launched a fashion line under her married name, "Lilly Pulitzer", and the rest is of course, preppy fashion history.

While the Bostwick heiresses were burnishing the family name through their accomplishments and style Stateside, it was quite a different story on the other side of the Atlantic, where the name garnered more salacious associations.

On May 2nd, 1892 the New York Times announced the engagement of Frances (Fannie) Evelyn Bostwick, Jabez and Helen’s youngest daughter, to a Scottish officer of the Royal Irish Rifles named Capt. Albert Carstairs. The next day, a discrete correction appeared, noting that similar announcements had been several times up to year before about her and subsequently denied each time. The paper made no note of their retraction however a short time later in June, when subsequently reporting their marriage, held at the Friedham, as one of the most significant in society that month, her being popular member of the “ Hunting Set”, known for her vivacity and beauty. The Carstairs settled in Mayfair, where Fanny quickly made her mark in London, eventually becoming a lady in waiting to Queen Alexandra – quite a feat for an American of “new money”. Fanny gave birth to a daughter named Marion Barbara (nicknamed Joe) in 1900, a week after her husband re-enlisted to serve in the Boer War. Rumors of affairs on Fanny’s part had swirled around for some time, and more than one gossip whispered doubts as to Capt. Carstairs being the biological father.

In December 1902, the New York Times reported that Captain Carstairs had been granted a divorce from his wife, obliquely mentioning a co-respondent, the playwright Francis Francis, with whom Fanny had been traveling to Monte Carlo and Homburg whilst her husband while her husband was off fighting in the Boer War. The Sun rose to her defense, stating, “It was no surprise to New Yorkers to learn that he and his wife were in the English divorce courts.” Going on to say “She was beautiful and was an heiress when the marriage took place, eleven years ago. It was a love match, as Capt. Carstairs was poor and socially in little better position than were many of Mrs. Carstairs admirers here.”

Fanny married her playwright soon thereafter, earning her the distinction of being now known as Frances, Mrs. Francis Francis if nothing else. The couple had two children, Evelyn Francis and Francis Jr. in quick succession. The marriage did not last however, with Fanny divorcing Francis to marry French aristocrat, le Comte Roger de Perginy. While racking up wedding bands, Fanny became a very vocal anti-suffragette. She also became keenly interested in science, the theories of one Russian–French surgeon named Serge Voronoff, who become famous in the 1920s and 1930s for his practice of transplanting monkey testicle tissue in particular into male humans for the claimed purpose of rejuvination. Evelyn funded his research, acted as his laboratory assistant at the Collège de France in Paris, and co-authored a book with him. It surprised no one when he became her 4th husband in 1920 (having earlier her Count, citing infidelity, of all things). That same year her mother Helen died, leaving Evelyn a very rich woman. Unfortunately, animal glandular rejuvenation or no, Fanny didn’t last long enough to enjoy her new marriage or immense wealth, dying in March 1921.

Fanny’s death liberated her daughter Joe, with whom she shared a strained relationship. Before Frances died, Joe married a childhood friend, the French aristocrat Count Jacques de Pret in 1918 so she could access her trust fund independently of her mother. No longer needing her mother’s permission for anything, the marriage was immediately annulled on the grounds of non-consummation; she renounced her married name and resumed using the name Carstairs.

Joe lived a bold, independent life. She habitually dressed as a man and had her arms tattooed. An open lesbian, she had affairs with Dolly Wilde(Oscar Wilde's niece) and a number of famous actresses, including Greta Garbo, Tallulah Bankhead and Marlene Dietrich. During Worl War 1, she served in France with the American Red Cross driving ambulances. In 1920, she started the 'X Garage, a car-hire and chauffeuring service featuring a women-only staff of drivers and mechanics. Carstairs lived in a flat above the garage (along with various friends and lovers). X Garage specialized in long-distance trips taking grieving relatives for visits to war-graves and former battlefields in France and Belgium, as well as short trips within London. During the early 1920s, X-Garage cars were a familiar sight in fashionable circles having an arrangement with the Savoy Hotel, among other clients, taking guests to the theatre, shopping, etc.

She habitually dressed as a man and had her arms tattooed. An open lesbian, she had affairs with Dolly Wilde(Oscar Wilde's niece) and a number of famous actresses, including Greta Garbo, Tallulah Bankhead and Marlene Dietrich. During Worl War 1, she served in France with the American Red Cross driving ambulances. In 1920, she started the 'X Garage, a car-hire and chauffeuring service featuring a women-only staff of drivers and mechanics. Carstairs lived in a flat above the garage (along with various friends and lovers). X Garage specialized in long-distance trips taking grieving relatives for visits to war-graves and former battlefields in France and Belgium, as well as short trips within London. During the early 1920s, X-Garage cars were a familiar sight in fashionable circles having an arrangement with the Savoy Hotel, among other clients, taking guests to the theatre, shopping, etc.

In 1925, after fully inheriting her large fortune through her mother and grandmother’s wills outright, she purchased her first motor boat motor boat. Between 1925 and 1930, Carstairs and became a very successful powerboat racer, taking the Duke of York's trophy and establishing herself as the fastest woman on water. Around the same time she was also given a doll by a girlfriend, naming it Lord Tod Wadley. Although the girlfriend didn’t last, Lord tod Whatley became her lifelong companion.

Around the same time she was also given a doll by a girlfriend, naming it Lord Tod Wadley. Although the girlfriend didn’t last, Lord tod Whatley became her lifelong companion.

Carstairs was also very generous to her friends, using her fortune to assist several male racing drivers and land speed record competitors. She purchased the island of Whale Cay in the Bahamas for $40,000 in 1934, building a lighthouse, school, church, and cannery for the islands population. She later expanded these properties by buying some surrounding islands as well. Dubbed “The Queen of Whale Cay” she lavishly hosted guests such as Marlene Dietrich,and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor there. Lord Tod was always at her side, and many of the islands superstitious natives believed the doll had magical powers. After living a wild and fast (on both land and water), Carstairs sold Whale Cay in 1973, after which she moved to Miami, living a considerably quieter life until her death in 1993. She was created with Lord Tod Wadley.

Lord Tod was always at her side, and many of the islands superstitious natives believed the doll had magical powers. After living a wild and fast (on both land and water), Carstairs sold Whale Cay in 1973, after which she moved to Miami, living a considerably quieter life until her death in 1993. She was created with Lord Tod Wadley.

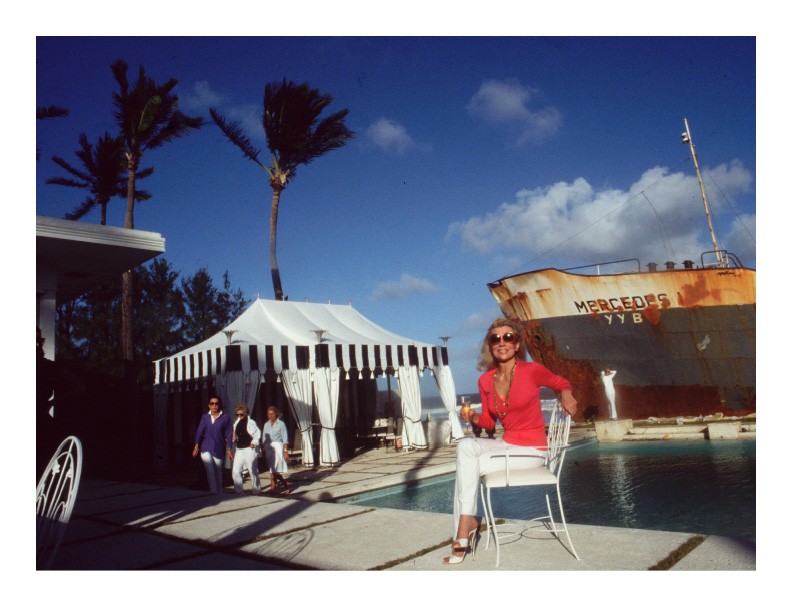

Florida, boats, and notoriety, all lead us to one last lady, a Bostwick briefly by marriage, not birth. Albert C Bostwick Jr, a nephew of Dorothy and Lillian, took as his bride the vivacious Mollie Natcher Bragno in 1960. The two were high profile fixtures on the New York/Saratoga/Palm Beach Social circuit before divorcing ten years later. The former Mrs. Bostwick (then Wilmot) later made waves in 1983, when she woke up on thanksgiving morning after a Tropical storm to find Venezuelan Oil in her swimming pool. Nonplussed, she served finger sandwiches and caviar and coffee to the crew, martinis to the scores of journalists who showed up while gamely posing for photographers, with true Bostwick élan.

The two were high profile fixtures on the New York/Saratoga/Palm Beach Social circuit before divorcing ten years later. The former Mrs. Bostwick (then Wilmot) later made waves in 1983, when she woke up on thanksgiving morning after a Tropical storm to find Venezuelan Oil in her swimming pool. Nonplussed, she served finger sandwiches and caviar and coffee to the crew, martinis to the scores of journalists who showed up while gamely posing for photographers, with true Bostwick élan.