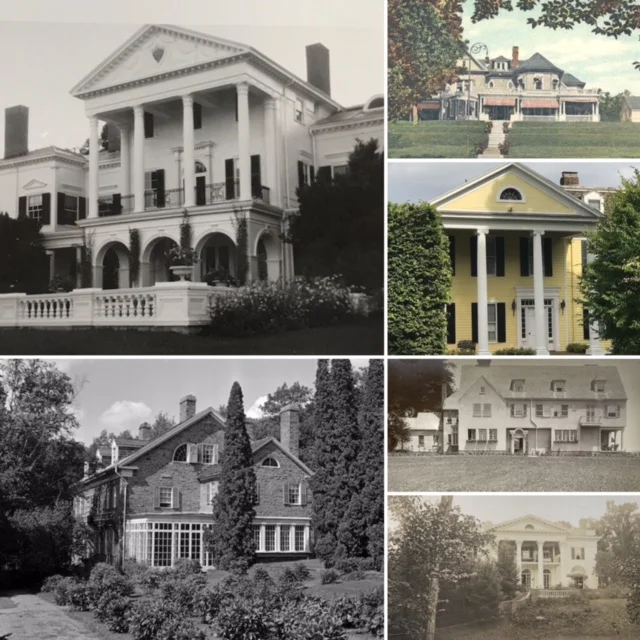

Alva's Collection: Buildings associated with the woman who "loved being knee-deep in mortar"

Alva Erskine Smith Vanderbilt Belmont was arguably one of the most formidable women of the Gilded Age, and much has been written in connection with her life and accomplishments. In this post we will look at just one aspect, as a person who “loved nothing better than to be knee deep in mortar" and the first woman admitted into the American Institute of Architects. To follow is a brief overview of many (but by no means all) buildings she lived in or had a hand in designing.

Mobile Alabama

Born in 1853 to a prosperous southern family, Alva Erskine Smith’s earliest memories were of this comfortable home in Mobile Alabama. It is interesting to note the gothic revival detailing on its exterior, a style that Alva would employ to dramatic effect in many of the homes she created as an adult.

40 Fifth Avenue

40 Fifth Avenue seen at far left (the second empire roof likely a later addition)

At the age of four her father moved his family to New York, settling into a home at 40 Fifth Avenue, smack dab in the heartland of the city’s Knickerbocracy. The Smiths moved to Europe after the Civil War, returning several years later, their residence listed at 14 West 33rd St, undoubtedly in one of the uniform brownstone townhomes that Alva would later profess to abhor.

Alva as a young woman

Idle Hour

Alva didn’t have to languish in brownstone ubiquity for long however, thanks to her marriage to William K Vanderbilt in 1875. In 1877 William’s grandfather, Commodore Vanderbilt died, leaving him $3 million outright. With part of their windfall they began building a country retreat in Islip Long Island named Idle Hour. Begun in 1878 and completed the following year, Idle Hour has dual significance. Not only was it the first home that Alva was directly involved in the design of, it also marked her first collaboration with architect Richard Morris Hunt. Despite appearing to be a fairly standard expression of the stick style then in vogue, Alva remembered this first project of hers proudly, later describing the house as without pretention, spacious and comfortable.

St Marks Islip

In the course of developing her estate, Alva found the local Episcopal Church her family was supposed to attend there lacking aesthetically. In short order, she paid to have it razed and erected a new one in its place. The resulting Norwegian-inspired wooden structure designed by Richard Morris Hunt gives a hint of the fantastic fruits the Vanderbilt/Hunt partnership would soon bear and remains a local landmark to this day.

660 Fifth Avenue

To fully appreciate the effect 660 Fifth had, it is good to look at it next to the neighboring brownstones

Alva and Hunt worked together on her famed French Renaissance style château at 660 Fifth Avenue between 1877 and 1881. Completed in 1882, this pinnacle of their artistic expression immediately sent shockwaves through New York Society, raising the architectural bar for new homes built by Manhattan’s elite. Likewise, her famed masquerade ball to formally open the home in 1883 catapulted the Vanderbilt’s firmly to the top of Gotham’s social pyramid.

Alva in costume for her ball

Marble House

After his father William Henry died in 1885, William K Vanderbilt was no longer merely rich, but a multi-millionaire to the tune of tens of millions. As a gift for his wife’s fortieth birthday, he called upon Hunt to design a new cottage for her in Newport. The resulting masterpiece inspired in part by the Petit Trianon, was completed in 1892. The final cost, widely reported as $11 million, while perhaps exaggerated, was undoubtedly much more than William could have originally imagined. Knowing Alva’s personality, this might have been intentional, for by the time the cottage was complete, cracks had already begun to appear in the Vanderbilts’ marriage

24 East 72nd Street

The couple separated in 1894 and divorced the next year. On top of Marble House, which she already owned outright, Alva reputedly walked away $10 million richer as well. It is said William also offered her 660 Fifth Avenue, but she demurred, purchasing a townhouse at 24 East 72nd street instead. It was from there that her daughter Consuelo left for her ill-fated nuptials to the Duke of Marlborough and where she wed her second husband, Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont, in 1896.

Belcourt Castle

Oliver brought Belcourt Castle, his own Hunt–designed Newport cottage, into the marriage. Alva decided to move into the Louis XIII-style hunting lodge, shuttering Marble House (except for its laundry facilities, which she found superior), and added bedroom suites for herself and her youngest son Harold to the mansion. Though Richard Morris Hunt had died in 1895, his sons carried on their father’s legacy through their architectural firm of Hunt & Hunt. Alva tapped them for the alterations to Belcourt.

Brookholt

Alva soon had Hunt & Hunt hard at work designing a new mansion and other buildings for the Belmont’s new estate on Long Island as. Built in 1897, Brookholt’s Colonial revival neoclassicism was a departure from Alva’s previous homes, which exhibited marked French influences. It was here that Oliver passed away in 1908 after an emergency appendectomy.

477 Madison Avenue

At the time of Oliver’s death, the Belmont’s were in the midst of construction of a new Hunt and Hunt designed residence on the corner of Madison Avenue and 51st Street, influenced by Inigo Jones’ Lindsey House in London. As a monument to him, Alva had an annex built containing a large gothic hall to house a portion of Oliver’s medieval armor collection. She and her son Harold moved into the house in 1909.

Belmont Mausoleum

For Oliver’s final resting place at Woodlawn Cemetery, Alva once again turned to France for inspiration, having Hunt & Hunt design a replica of the Chapel of St. Hubert in Amboise, France.

Chinese Tea House

Although Oliver left her Belcourt (not to mention another $10 million) after his death, Alva moved back across the street to Marble House. Bitten by the building bug again, in 1912 she asked Hunt and Hunt to design a Chinese style teahouse for her on the grounds. Completed in time for the 1914 season, Alva opened it with an elaborate Oriental themed costume ball, today remembered as one of the last great Newport entertainments of the twilight of the Gilded Age.

The Chinese Ball, Alva is seated front row, second from right

Beacon Towers

After Alva sold Brookholt in 1915, she built her last original architectural creation with Hunt and Hunt between 1917 and 1918. The result, Beacon Towers was a castle overlooking Long Island Sound at Sands Point. It was pure fantasy, drawing upon references including Moorish Castles in Spain and illustrations found on the pages of medieval illuminated manuscripts. The theatrical result was historically referenced while interestingly modern at the same time. Many believe the mansion inspired F Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby.

Villa Isoletta, Chateau d'Augerville

The 1920s found Alva spending more and more time in France, taking an apartment in Paris at 9 Rue du General Lambert. She sold her Madison Avenue townhouse in 1923, Beacon Towers in 1927, and eventually even Marble House itself. She purchased two new properties in France. Villa Isoletta, at Eze-sur-Mer on the Riviera

Villa Isoletta

and Chateau d’Augerville (said to be one of the inspirations for 660 Fifth Avenue), which became her primary residence.

Chateau d'Augerville

As exquisite as the Chateau was, Alva could not resist improving on it. She had the river flowing through the estate widened because as she said, "This river is not wide enough", brought in paving stones from Versailles to cover the forecourt, and built a neo-Gothic portal separating the entrance of the château and village from the surrounding farmland. It was here that Alva passed away in 1933.